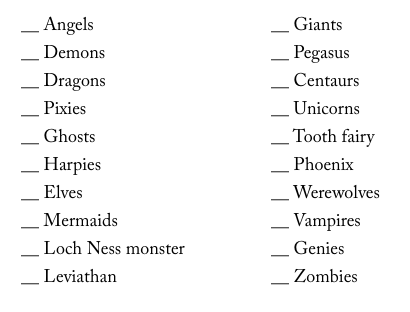

This morning while I ate my breakfast and flipped through my copy of the New Yorker, I came across an interesting article titled Fantastic Beasts and How to Rank Them. Usually I breeze through the New Yorker, smirking at the cartoons and at best skimming an occasional article. This one caught my eye because in between blocks of text it included this list which looks like it came straight out of one of the little brown books:

I flipped back to the start of the article and ended up reading the entire thing. It certainly wanders about a fair bit, but the central core of it is trying to make sense of the idea that we as humans are capable of ranking the plausibility of a list of things that are objectively all completely implausible. While this is interesting as a general observation about the human condition, what really grabbed me was a small part where the author explored why we would even bother to do so. Writers and artists, she claims, “have practical motives for wondering how best to make imaginary things seem convincing.” She gives some examples including Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Walt Disney’s practice of having his artists take life drawing classes to add realism, and concludes “Taken together, Disney’s foundation of fact and Coleridge’s semblance of truth suggest a good starting place for any Unified Theory of the Plausibility of Supernatural Beings: the more closely such creatures hew to the real world, the more likely we are to deem them believable.”

I think this concept, which Picasso put as “learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist” applies equally well to gaming. In fact, I think this is what is so appealing about concepts like Gygaxian Naturalism, or Delta’s sometimes overly detailed ballistics research (I kid because I love). In essence, it is the first golden rule which Delta details as:

The highest degree of realism has been attempted (so long as it does not interfere with the flow of the game).

I love that statement for the strange juxtaposition of listing the primary concern, flow of the game, as secondary in the statement, even so far as making it parenthetical. What a wonderful use of language and punctuation to illustrate that the secondary concern, high degree of realism, while secondary is still hugely important.

I think about these things a lot when writing content. Lest I fall into the trap of “murder at the zoo” style dungeons, I ask myself why this creature or NPC is here? What is its day-to-day patterns? Sure, I pull short of putting bathrooms in every single dungeon, and sometimes the motivations of the NPC must be comically Machiavellian, but still they exist. Nothing breaks the mood of a game quite like jumping the plausibility shark, but that line can be very hard to find in such a fantastic world. Why for example are we OK with mermaids but sea lions strike us as ridiculous? No, not those sea lions, these:

I don’t really have answers for how and where to draw the line, but do feel free to read the above linked New Yorker article which does a pretty reasonable job. I suspect it all comes down to the specific individuals at the table. And to that end, the best advice I can give is that given to me by my high school drama teacher: “always play to the top of the audience.”

What vexes me about this thought experiment is the underlying linguistic miracle that, even before we can rank these imaginary creatures, we can somehow agree on what we’re ranking. The words used in the list have no real-world referents, except perhaps in the most abstract “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” sense. There are, for example, no real dragons, and so there is nothing objective to anchor *anyone’s* interpretation of what a “dragon” is. Probably for that reason, artistic interpretations of “dragon” are as numerous and varied as pebbles on a beach — and yet, were each of us to sit down and fill in the blanks on the list, we all could probably stick “dragon” somewhere relative to everything else on the list. In the context of running a game, how does one account not only for the fact that each of us will see different creatures as comparatively more or less realistic, but also for the fact that there is no way to know what, precisely, people think of when they think of a creature? If the “dragon” I see in my head is different from the “dragon” you see in yours, why should my view of how realistic a dragon is be any more or less valid than yours? It makes my head spin that we are ever able to entertain ourselves with imaginary things at all, instead of just breaking down into fistfights over what “dragon” means.